|

Doriopsilla janaina

DORIOPSILLA JANAINA

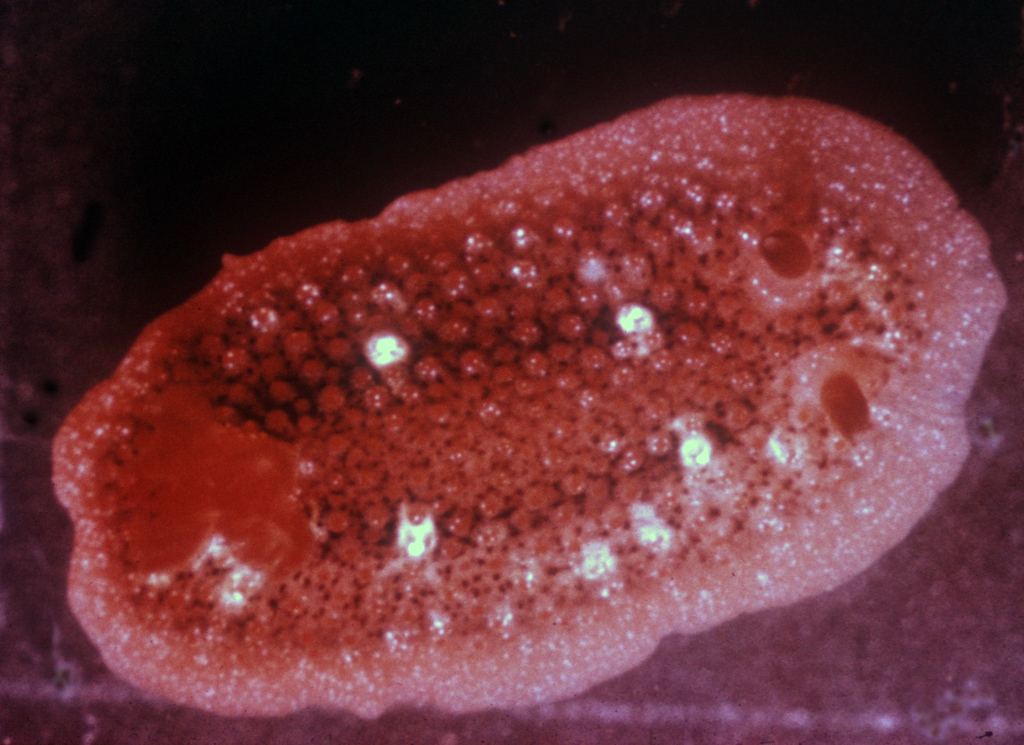

Historic photo by Frederick M. Bayer (1962)

Individual collected at Perico Island, Ft. Amador, Panama Canal Zone

Under rocks at low water, 25 December 1962

Doriopsilla janaina Marcus & Marcus, 1967

This intriguing, colorful little dorid was originally named from specimens collected at Ft. Kobbe and Ft. Amador in the Panama Canal Zone by Dr. Frederick M. Bayer and colleagues in 1962 and 1963. The Marcuses used one of his photographs (photograph above) to describe the color and external morphology of the living animal:

“The color alive, from the photo, is light red. Two blackish bands, which have a common origin between the rhinophores, end under the branchial tuft, and leave the tubercles free. Minute white dots on the blunt tips of the latter are cutaneous glands. Around the base of every tubercle, except the quite marginal ones, there are about five black spots, evidently single melanophores. There are two pairs of bigger white tubercles and many small, dark red spots, the latter especially in the middle. The rhinophores are dark red with small white tips, and white dots occur on the rim of the rhinophoral pits. The black pigment is retained after preservation; the white glandular secretion and the red color have disappeared. The absence of black pigment in the inner organs contrasts with several other dendrodoridids.” (Marcus & Marcus, 1967: 97-98; Canal Zone, two specimens)

They also reported its occurrence in the upper Gulf of California:

“In the photograph the pink color of the notum and the generally white, but sometimes dark red tips of the tubercles are most conspicuous. The bases of the tubercles are surrounded by black dots, especially large in one median and two lateral bands between gills and rhinophores, and confluent in front. Two pairs of white blotches, evidently consisting of secretion, lie on the sides. The lateral tubercles are smaller than those in the middle. The rhinophores are red, the gills orange, the borders of the rhinophoral pits and the branchial pocket are white. The hyponotum is transparent, showing the bundles of spicules.” (Marcus & Marcus, 1967: 205; Puerto Lobos, Sonora, Mexico, five specimens)

This color form I term (for want of a better phrase) “Classic Pink.” A sample of other specimens demonstrated some degree of different black and white speckling. Based on the literature and my own collecting observations, there seem to be two other color variations, “Galápagos Yellow,” and “Variegated.”

The “Galápagos Yellow” has been collected in the Islas Galápagos (Camacho-Garcia, Gosliner & Valdés, 2005); I have found it at Bahía de los Ángeles; Behrens & Hermosillo (2005) used that color form in their book.

Camacho-Garcia et al., wrote, “Color yellow, orange or pale red, with small black spots. Tubercles surrounded by opaque white rings. Rhinophores and branchial leaves yellow or orange, with white apices” (page 79). They reported its occurrence from Baja California, Mexico, to Panama and the Galapagos. Behrens & Hermosillo (page 88) wrote, “The notum is covered with small tubercles, and varies from yellow to red or brown. There is a dark circular band mid-dorsally. Within this band are two pairs of large white tubercles forming a square. There are lighter colored tubercles between these.”

“Variegated” is known from Ecuador and Bahía de los Ángeles. Its coloration is a cream whitish notum, with light orange-pink marginal band, sprinkled liberally with black and snow white dots. Tubercles are cream basally, tipped in orange-pink with snow white spots.

So, what do we have? These variations are not allopatric. The question is, “How biologically true or significant are these “categories”? Are they just color forms of one species? Or do we have a situation like that found in other Doriopsilla complexes, with synonymies and unnamed cryptic species, with DNA determinations needed to figure things out? It just warrants that platitude everyone uses: “Further work is needed.” Yes, you heard it from Techno Hans, it will require some DNA analysis to sort out the situation, plus internal anatomical descriptions.

Literature Cited

Behrens, David W. & Alicia Hermosillo. 2005. Eastern Pacific Nudibranchs. A Guide to the Opisthobranchs from Alaska to Central America. Sea Challengers, Monterey. vi + 137 pp.

Camacho-García, Yolanda, Terrence M. Gosliner & Ángel Valdés. 2005. Field Guide to the Sea Slugs of the Tropical Eastern Pacific. California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco. 129 pp.

Marcus, Eveline & Ernst Marcus. 1967. American Opisthobranch Mollusks. University of Miami Institute of Marine Sciences, Studies in Tropical Oceanography No. 6: 256 pp.

Imperial Beach, Calif

Jan., 2015

Send Hans email at hansmarvida@sbcglobal.net

|

Doing science is often considered to consist of four components: Observation, Hypothesis, Experimentation, and Theory. However, this misses the final, crucial point, without which science is not science: that is Communication. One must publish, present, teach or discuss the findings for it to be science. So science education (beginning with the youngest ages) is inherently part of a scientist's job description. I acknowledge the help of my nine-year-old granddaughter Ivette on some of my research expeditions, where she helps, observes, does and learns science. As she is shown doing here at Bahía de los Ángeles.

Children belong in the field. Once Ivette and I were traveling over a dirt road in my Jeep, with visibility nearly zero because of the billowing dust. I told her I did not know where this trail would end up, and she said, "No importa, Tata. ¡Si encontramos algo nuevo, podemos explorar!" "It doesn't matter, Tata. If we find something new, we can explore!" As scientists, we may not know what we are looking for, but we'll know it when we find it, based on our "thoroughly conscious ignorance" (James Maxwell).

Imperial Beach, Calif

Jan., 2015

Send Hans email at hansmarvida@sbcglobal.net