|

Hypselodoris ghiselini

Photo courtesy of Jim Pavletich

Isla San Jorge south east of Puerto Penasco, Sonora, Mexico

12 May 2012

Hypselodoris ghiselini Bertsch, 1978

TAXONOMY

Above species-level classifications are not pigeon-holes into which groups of animals are clumped, but should reflect common descent among organisms (Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species, chapter XIV). Hence, the study of taxonomy itself evolves based on our better understanding of the phylogenetic relationships among organisms. This often results in changing generic placements of well-known species (e.g., Laila cockerelli MacFarland, 1905, is now Limacia cockerelli).

The 300+ described species of Chromodorididae nudibranchs are an excellent example of such developments. Pruvot-Fol (1951), Bertsch (1977), Rudman (1984), Gosliner & Johnson (1999) and others have used traditional morphological features such as the radula, reproductive system and coloration to determine generic affinities. In April 2012, Rebecca Johnson and Terry Gosliner published a molecular phylogeny and new classification of the chromodorids. It is the most significant and comprehensive revision to date of this clade. They sequenced mitochondrial markers (16s and COI) of specimens from over 150 species, recognizing 16 genera within the family:

Cadlinella Thiele, 1931

Tyrinna Bergh, 1898

Noumea Risbec, 1928

Diversidoris Rudman, 1987

Glossodoris Enrenberg, 1831

Ardeadoris Rudman, 1984

Chromodoris Alder & Hancock, 1855

Goniobranchus Pease, 1866

Dorisprismatica d’Orbigny, 1839

Felimida Marcus, 1971

Miamira Bergh, 1875

Ceratosoma Adams & Reeve, 1850

Felimare Marcus & Marcus, 1967

Hypselodoris Stimpson, 1855

Mexichromis Bertsch, 1977

Thorunna Bergh, 1878

On a personal note, the only two living folks who have named a chromodorid genus are Bill Rudman (Australian) and myself (Californian). But this too shall pass.

The Johnson & Gosliner (2012) new classification changed over 50% of the traditionally-accepted placements. Of significance to our discussion of this week’s BOW, they placed the well-known Hypselodoris agassizii (Bergh, 1894) and H. californiensis (Bergh, 1879) into the genus Felimare. They considered H. ghiselini to be an hypothesized member of this genus. While I am in substantial agreement with their new classification, and evidence may well eventually be presented to confirm this, for the purposes of this site, it seems most appropriate to retain this species within Hypselodoris, with the obvious caveat it will most probably be proven to be Felimare ghiselini at some future date.

RADULA: SCANNING ELECTRON MICROSCOPY, LINE DRAWINGS and MERISTICS

This species was one of the first 10 species of nudibranchs named using SEM to illustrate the radula. During those pioneering years, “charging artifacts” (bright, burned-out regions on the micrograph image; see Bertsch et al., 1973: 290) were too common. The linked SEM images, SEM 01 , SEM 02 , SEM 03 , SEM 04 , SEM 05 , are from the original images, cropped and brightness/contrast manipulated to reduce the artifact distraction. At that time, my standard practice was to include traditional line drawings from light microscopy of individual teeth. The most immediate advantage of SEM is that it gives a perspectival image of the structural arrangements between multiple teeth (both within and between rows).

In addition to the radular illustrations, in my original description of this species I analyzed the meristic characters of 23 radulae, for which I presented a combined radular formula of 43-85 (50-128.0.50-128), showing the range of variation in tooth and row counts. As is typical for most radular-bearing spongivorous dorids, there is a positive correlation between the number of tooth rows and the number of teeth per row (Bertsch, 1976). Regrettably, most descriptions of new species lack such a quantity of material to show the extent of intra-specific radular variation. Nevertheless, because of today’s onslaught against and loss of global biodiversity, and for other conservation issues, it is important to identify and name faunal units (=species), even based on limited numbers of specimens.

BIOGEOGRAPHY and ENDEMISM

As stated in my previous BOW (June 2001), this species occurs throughout the Gulf of California, from Puerto Peñasco, Sonora, to La Paz, Baja California Sur. My records of sightings indicate it is more common in the southerly waters of the Gulf. During a 10-year study period (January 1992-December 2001) at Bahía de los Ángeles in the mid-upper Gulf (approximately 29º 03' N; 113º 32' W), only 16 specimens were observed (Bertsch, 2008); curiously, 12 were reported during the first three years (January 1992-1995). In contrast, during a one-month diving period, June 1985, in the Las Arenas area (to the southeast of La Paz, approximately 24º 02' N; 109º 49' W), I recorded 61 Hypselodoris ghiselini.

All known records of this species are from within the Gulf of California (see Bertsch, 1978, for an extensive, although dated, list of site records), and hence it appears to be a Gulf endemic. There are 116 known (including undescribed) species of nudibranchs in the Gulf of California (Bertsch, 2010). At this time, six species (5.2%) are endemic: Acanthodoris pina Marcus & Marcus, 1967; A. serpentinotus Williams & Gosliner, 1979; Conualevia marcusi Collier & Farmer, 1964; Hypselodoris ghiselini Bertsch, 1978; Dendrodoris stohleri Millen & Bertsch, 2005; and Cuthona longi Behrens, 1985.

The type locality of this species is Las Cruces, BCS (24º 13' N; 110º 05' W). Professor Mike Ghiselin and fellow UC Berkeley grad student John Allen were snorkeling with me when the type specimen was obtained. I remember that trip well. We had collected a number of spiny lobsters, which Mike used to teach us a non-credit course on marine gastronomy! Las Cruces is also the type locality for Aglaja regiscorona Bertsch, 1972 (reports from the Indo-Pacific for this species are most likely erroneous), and Phidiana lascrucensis Bertsch & Ferreira, 1974.

NATURAL HISTORY

Although the prey of Hypselodoris ghiselini is unknown, it may well be euryphagous on several sponge species, an exception among members of this group. This species differs chemically from Felimare agassizii and F. californiensis. The latter two species sequester only furanosesquiterpenoids, but four metabolites are found in H. ghiselini (Cimino & Ghiselin, 2009).

Mike Ghiselin succinctly defined natural selection: “The basis of evolution is guts and gonads.” They survive on their food and pass on their genetic variation. Obviously, copulatory behavior is interesting and important.

On the morning of 12 May 2012, Jim Pavletich was scuba diving in 29 feet of water at Isla San Jorge (31º 00' 43" N’ 113º 15' 47" W), 26 miles SE of Puerto Peñasco, Sonora. The water temperature was 72º F. He encountered a pair of Hypselodoris ghiselini flagrante delicto conjoined. Over a period of two minutes he took a sequence of PC Video (33megs) ,MAC Video (27 megs) photos of their copulation, until they ultimately separated and crawled their separate ways. No further comment is needed by me on these stop-action shots! In submitting this series of photos, Jim apologized to Webmaster Mike Miller, “Too bad for me I did not know what I was photographing till it was too late to get a video.” But these photos do JUST FINE!

He used a Canon Powershot A640 camera in a Canon case. The photos were taken without flash, at F-stop 2.8-3.5, 1/40-1/60 second, -0.7 exp.

Thank you Jim for letting us present your record into the private life of Hypselodoris ghiselini.

LITERATURE CITED

Bertsch, Hans. 1976. Intraspecific and ontogenetic radular variation in opisthobranch systematics (Mollusca: Gastropoda). Systematic Zoology 25 (2): 117-122.

Bertsch, Hans. 1977. The Chromodoridinae nudibranchs from the Pacific coast of America. Part I. Investigative methods and supra-specific taxonomy. The Veliger 20 (2): 107-118.

Bertsch, Hans. 1978. The Chromodoridinae nudibranchs from the Pacific coast of America. Part IV. The genus Hypselodoris. The Veliger 21 (2): 236-250.

Bertsch, Hans. 2008. Opistobranquios. In: Gustavo D. Danemann & Exequiel Ezcurra (eds.). Bahía de los Ángeles: Recursos Naturales y Comunidad. Línea Base 2007. SEMARNAT, Pronatura Noroeste, SDNHM & INE. Capítulo 11: 319-338.

Bertsch, Hans. 2010. Biogeography of northeast Pacific opisthobranchs: Comparative faunal province studies between Point Conception, California, USA, and Punta Aguja, Piura, Perú. In: Rangel Ruiz, Luis José, Jaquelina Gamboa Aguilar, Stefan L. Arriaga Weiss & Wilfrido M. Contreras Sánchez (eds.). Perspectivas en Malacología Mexicana. Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco, Villahermosa, México. pp. 219-259.

Bertsch, Hans, Antonio J. Ferreira, Wesley M. Farmer & Thomas L. Hayes. 1973. The genera Chromodoris and Felimida (Nudibranchia: Chromodorididae) in tropical west America: Distributional data, description of a new species, and scanning electron microscopic studies of radulae. The Veliger 15 (4): 287-294.

Cimino, Guido & Michael T. Ghiselin. 2009. Chemical defense and the evolution of opisthobranch gastropods. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 60 (10): 175-422.

Gosliner, Terrence M. & Rebecca Johnson. 1999. Phylogeny of Hypselodoris (Nudibranchia: Chromodorididae) with a review of the monophyletic clade of Indo-Pacific species, including descriptions of twelve new species. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 125: 1-114.

Johnson, Rebecca Fay & Terrence M. Gosliner. 2012. Traditional taxonomic groupings mask evolutionary history: A molecular phylogeny and new classification of the chromodorid nudibranchs. PloS ONE 7 (4): e33479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033479.

Pruvot-Fol, Alice. 1951. Revision du genre Glossodoris Ehrenberg. Journal de Conchyliogie 91 (3 & 4): 76-164.

Rudman, W. B. 1984. The Chromodorididae (Opisthobranchia: Mollusca) of the Indo-West Pacific: A review of the genera. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 81 (2/3): 115-273.

Imperial Beach, Calif

Sept. 2012

Jim Pavletich

|

I worked for the government for 36 years finishing my career as the Social Security Administration Public Affairs Officer for Arizona. My wife and I currently operate our own business "Social Security Consultants." I have been diving since 1980 and am a PADI Divemaster and SSI Dive Control Specialist.

|

|

|

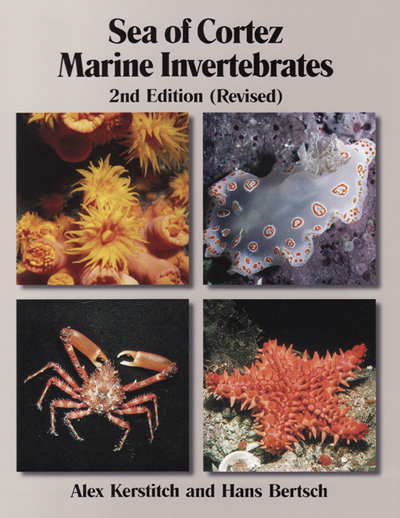

Personally autographed copies of Sea of Cortez Marine Invertebrates, 2nd edition, are available from Hans.

Send Hans email at hansmarvida@sbcglobal.net to order or obtain more information! |