|

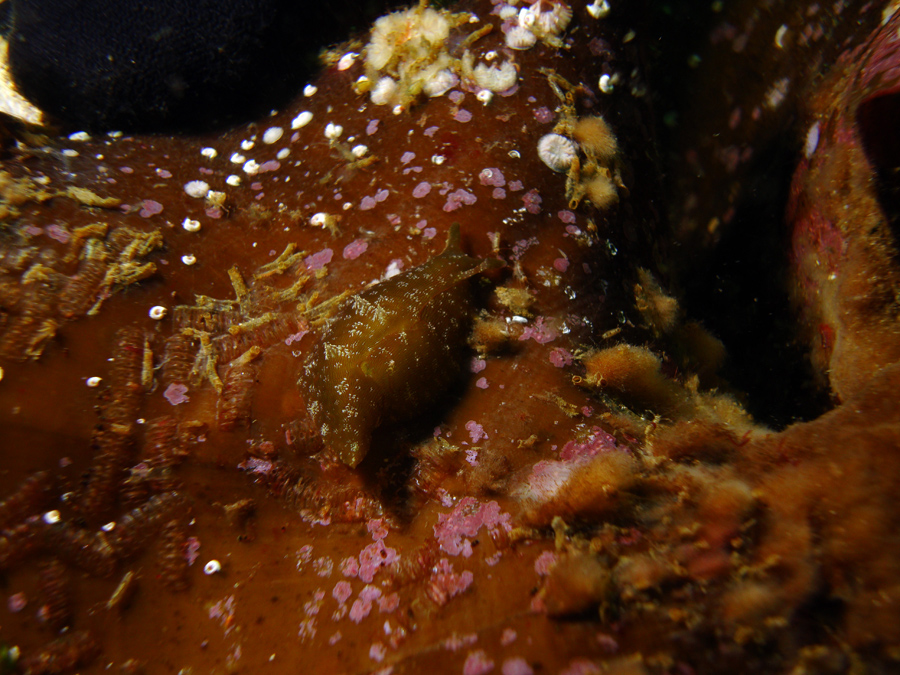

Phyllaplysia padinae

Photo by Dr. Christopher L. Kitting

Plyllaplysia padinae Williams & Gosliner, 1973

This is a highly cryptic species, that may be more common than collecting records suggest. One has to carefully flip through lots of dense leaves of Padina to find it, usually seasonally when Padina is growing. That probably accounts for why it was only known from a few localities in the upper Sea of Cortez for almost 25 years. Today it is known to range from Puerto Peñasco, Sonora, south to Bahía de Banderas, Jalisco/Nayarit, to Costa Rica and Panamá (see Hermosillo, Behrens & Ríos-Jara, 2006). Chris Kitting and I found specimens and egg masses of Phyllaplysia padinae last March, while scuba diving on the reef between Islas Ventana and Cabeza de Caballo, at Bahía de los Ángeles.

The Padina Seahare “is olive-green to brownish green with random white spotting on the dorsal surface. Some specimens have a few variably shaped papillae, with multiple tips. This species also crawls with a leach-like movement” (Behrens & Hermosillo, 2005: 36). Its flattened body has an elongate-oval shape. This contrasts with the long and narrow body of its northern allopatric congener, Phyllaplysia taylori Dall, 1900, which has adapted to live on the slender blades of the eel grass Zostera (from Vancouver Island, British Columbia, to San Diego, California).

Its internal anatomy (including the radula, jaws and labial aperture, and the digestive, reproductive and nervous systems) and natural history were quite admirably described in the original description by Gary and Terry.

The flat, rectangular egg mass is laid on the Padina leaves in tight, back and forth, zig-zag rows . Additional illustrations, measurements and discussions of the egg masses of both Phyllaplysia padinae and Phyllaplysia taylori are found on Bill Rudman’s Sea Slug Forum (www.seaslugforum.net/showall/phylpadi and www.seaslugforum.net/showall/phyltayl ), and in Bertsch & Hirshberg (1973), Bridges (1975), Goddard (2004), and Goddard & Hermosillo (2008). As Jeff Goddard comments (Sea Slug Forum, Message 22665), the eggs of Phyllaplysia taylori “do not appear as dense as those of the more southerly P. padinae because they are much larger and develop directly into juveniles, while those of P. padinae develop into much smaller, planktotrophic veliger larvae.”

Forty Years Ago: Memories from the Expedition

In December 1970 five of us drove south from the San Francisco Bay Area to collect opisthobranchs at Bahía San Carlos, northwest of Guaymas, Sonora. The border-crossing town of Lukeville, Arizona , was still called Gringo Pass; the roads weren’t well paved, and the US village was even smaller than it is today. I had driven down with a Unitarian minister and his wife, then met up with the brothers Terry and Michael Gosliner and Gary and Scott Williams at their campsite on the beach. Bahía San Carlos was a glorified trailer park in the desert by the sea surrounded by cacti and volcanic spires. Most prominent were the 3-pronged sharp peaks of Tetas de Cabral , which had been the backdrop for the filming of the movie Catch-22! The intertidal location was just across the sand from the campsite.

“On December 23, 1970, some algal material (Padina sp.) was collected near San Carlos, Sonora, Mexico, to be used as a background for photographing several opisthobranch collected the previous day. It was noted, however, that another opisthobranch was crawling actively along the algal surface” (Williams & Gosliner, 1973: 216). I must confess that I had been chosen to bring back the background material to make our “tub shots” more authentic, while the rest of the team enjoyed their coffee. Walking back to our field lab, I saw the shadow on the Padina leaves that betrayed the unknown, hidden slug.

We passed the days there collecting on the low tides, and examining and photographing our finds. The lab bench was the hood of Terry’s borrowed Chevrolet. Although I don’t have our complete species list, I still have arcane Ektachrome shots we took of the Panamic Phidiana lascrucensis, the Californian Hermissenda crassicornis, and the Atlantic Tyrinna evelinae, crawling over faux-backgrounds in a straight-sided clear glass bowl. There were good reasons why my photographs of the holotype of Phyllaplysia padinae were not published in the original description!

At night we found refuge from the wild animals in a large walk-in tent. We heard loud rustling noises in the cacti come closer, and suddenly our tent was buffeted by a legendary Sonoran beef-on-the-hoof, out for an evening stroll. We bravely tossed pebbles over the tent to chase it off, but the beast returned later in the early morning hours to awaken us to the sound of it marking its territory on our tent stakes.

When we finally left for the return journey, every cubic centimeter of the car’s trunk was filled with gear and clothes, microscope, tent...well, you get the picture. The US border agent at Lukeville was horrified by the five dirty, smelly, salt-encrusted, hirsute “Berkeley-ites” giving him an inspection job that could easily last several hours. Our honest demeanor, and an official letter of our scientific certification by Allyn G. Smith of the California Academy of Sciences, caused him to mumble, “Close up the trunk and go. You may have something in there, but....” That evening we made a dry camp in the Arizona desert, sleeping bags spread out on the ground. We continued on the next morning to Gila Bend. Hungry student-scientists, we treated ourselves to breakfast at the spectacular, still-operating-today, Space Age Restaurant. Mock rockets in the parking lot and astronaut photos on the walls made for a distinctive motif, sure to attract passing tourists. Our young waitress proudly told us the nickname of the high school football team was the Gila Monsters. Luckily we had not encountered any of them the night before.

Forty years later, things have changed. Lukeville now has a state-of-the-art entryway, and the hills of Bahía San Carlos are covered with luxury retirement and vacation homes. But the Sea of Cortez remains for colleagues and friends to explore, regardless of the field conditions.

References

Behrens, David W. & Alicia Hermosillo. 2005. Eastern Pacific Nudibranchs. A Guide to the Opisthobranchs from Alaska to Central America. Sea Challengers, Monterey, California. vi + 137 pp.

Bertsch, Hans & Jerilyn Hirshberg. 1973. Notes on the veliger of Phyllaplysia taylori. The Tabulata (Santa Barbara Malacological Society) 6 (1): 3-5.

Bridges, C.B. 1975. Larval development of Phyllaplysia taylori Dall, with a discussion of development in the Anaspidea (Opisthobranchia: Anaspidea). Ophelia 14: 161-184.

Goddard, Jeffrey H.R. 2004. Developmental mode in opisthobranch molluscs from the northeast Pacific Ocean: feeding in a sea of plenty. Canadian Journal of Zoology 82: 1954-1968.

Goddard, Jeffrey H.R. & Alicia Hermosillo. 2008. Developmental mode in opisthobranch molluscs from the tropical eastern Pacific. The Veliger 50 (2): 83-96.

Hermosillo, Alicia, David W. Behrens & Eduardo Ríos-Jara. 2006. Opistobranquios de México. Guía de Babosas Marinas del Pacífico, Golfo de California y las Islas Oceánicas.CONABIO & Impre-Jal, Guadalajara, México. 143 pp.

Williams, Gary C. & Terrence M. Gosliner. 1973. A new species of anaspidean opisthobranch from the Gulf of California (Mollusca: Gastropoda). The Veliger 16 (2): 216-232.

Hans Bertsch

Imperial Beach, California

Send Hans email at hansmarvida@sbcglobal.net

at Bahía de los Ángeles, March 2010

|