|

Felimare ghiselini

Photograph of 38 mm long animal, taken 20 January 1984,

in 15 feet of water by Hans Bertsch

Puerto Chileno, Cabo San Lucas, Baja California Sur

IN MEMORIAM:

DR. MICHAEL T. GHISELIN

(13 May 1939-14 June 2024)

THREE SPECIES

Felimare ghiselini (Bertsch, 1978) [= Felimare californiensis (Bergh, 1879)]

Coloration of animal a deep navy blue. The notum is covered with numerous small, bright yellow specks. There are whitish-blue spots scattered on the notum, far less numerous than the yellow markings, and varying in number from just a few to over a dozen. Bottom of the foot is unmarked, a solid deep blue color. Rhinophores and gills 9-12) are navy blue, with yellow dots on the inner sides of the gills. Can reach 70 mm in total length. The original holotype measured 35 mm in length. It was collected by Michael T. Ghiselin at Las Cruces, Baja California Sur, 1 July 1974, while snorkeling with graduate students Hans Bertsch and John Allen. Its known distribution is throughout the Gulf of California.

The original description identified morphological features separating this species from Felimare californiensis (Bergh, 1879) and Felimare agassizii (Bergh, 1894); Bertsch (1978) also reported the sympatric occurrence of F. californiensis with F. ghiselini at Bahía de los Ángeles. Using an integrative analysis, combining morphological features with DNA determination and geographic occurrences, Hoover et al. (2017) synonymized F. ghiselini with F. californiensis. However they distinguished these two “taxa” based on distribution, with F. ghiselini being the southern form , restricted to the Gulf of California, and F. californiensis the northern form, ranging from the Gulf of California to the Southern California Bight, and rarely northward to Monterey. Felimare agassizii is clearly distinguishable from the other two species with its distinctive yellow and green lines along the sides of the notum, which are broken in the middle of the body. It is more southerly in distribution, ranging from the La Paz area to Panamá and the Islas Galápagos. In a long term ecological study at Bahía de los Ángeles, from 11 December 1981 to 17 December 2014, Bertsch found only one specimen of F. agassizii, and 61 specimens of the ghiselini/californiensis morphs. During several years of study, Orso Angulo and I observed 45 specimens of F. agassizii in the La Paz, Baja California Sur, region.

Nudibranchs stink. Well, actually they secrete metabolite compounds from their food prey which is used for their defense. Hochlowski et al. (1982) reported that “H. ghiselini from the Gulf of California contained a diterpene epoxide, ghiselinin, dendrolasin, nakafuran, and a related methoxy butenolide. H. californiensis from the Gulf of California contained dendrolasin and nakafuran, while specimens from San Diego, CA, contained furodysinin, euryfuran and pallescensin A....The sponge Euryspongia sp. was found to be the source of euryfuran.” Further studies on these differences in feeding ecology and their geographic distribution would certainly be informative.

Rostanga ghiselini

Gosliner & Bertsch, 2017A second eponym honoring Michael Ghiselin is also a Gulf of California endemic. The type locality is Punta Gringa, Bahía de los Ángeles, Baja California. This just happens to be the location where Mike underwent his open water scuba check-out dives.

The animal is about 30 mm in length. It body color is “red to reddish orange with a secies of large, well-spaced black spots present on the dorsal surface. The perfoliate rhinophores are conical with a series of 10-14 horizontal lamellae....The notum is covered with a series of densely packed caryophyllidia. Each caryophyllidium bears 5-6 calcareous spines” (Gosliner & Bertsch, 2017: 120).

Tritonicula hamnerorum (Gosliner & Ghiselin, 1987)

Mike first collected this species from Great Abaco Island in the Bahamas, while on a research trip with Bill and Peggy Hamner. A few months later, Terry and Mike were diving in Quintana Roo, México, and found additional specimens in massive congregations. They found 88 individuals crawling all over the underside of a detached gorgonian. Occurring in such a high density this species was given a secondary common name, “The Gorgonian Maggot.”

The animals had a medicinal smell, which Mike likened to camphor. Such a pungent odor comes from some interesting secondary compounds secreted by the nudibranch. Tritonicula hamnerorum has been found feeding on two species of sea fans, Gorgonia flabellum Linnaeus, 1758, and G. ventalina Linnaeus, 1758. The slugs contain, sequester and concentrate julieannafuran, a furano germacrene sesquiterpenoid. In feeding experiments, fish were found not to attack intact nudibranchs” (Cimino & Ghiselin, 2009: 307).

Adults can reach about 15 mm in length. The grayish dorsum is covered witgh a series of irregular thin white lines, which run the length of the body. Cerata are distinct, branched, and few in number. It is known through the Caribbean, from Florida, Quintana Roo, Mexico and Belize, to the Bahamas and Cayman Islands.

Based on DNA studies, this species was transferred from Tritonia to the new genus Tritonicula Korshunova & Martynov, 2020. Also included in their new genus were the eastern Pacific T. myrakeenae (Bertsch & Mozqueira Osuna, 1986) and T. pickensi (Marcus & Marcus, 1967) and the Caribbean T. bayeri (Marcus & Marcus, 1967). All four species of Tritonicula have small numbers of radular teeth, only up to 11 per half row.

EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGIST: A SCHOLAR AND A GENTLEMAN

Mike was born in Salt Lake City, Utah, 13 May 1939 and passed away in San Jose, California, 14 June 2024, having recently celebrated his 85th birthday. His parents, Olive (10 September 1907-7 February 2011) and Brewster (13 June 1903-11 June 2003) Ghiselin were both accomplished and well-recognized authors. She wrote short stories (see The Testimony of Mr Bones: Stories, 1989) and he was a poet (see Against the Circle, 1946). Brewster created the Utah Writer's Conference in 1947, where he remained its director until 1966. Michael had one brother, Jon Brewster Ghiselin (1935-1985), who was a professor of biology and ecologist. Mike’s sister-in-law Joan (Lager) Ghiselin (1936-1991) was a teacher and respiratory therapist. Mike is survived by his three nieces, Barbara Ghiselin Kay (husband David), Elizabeth Ghiselin Stein (husband Alex), and Katherine Ghiselin, and four grand nieces and nephews, Nina, Miranda, Oliver, and Jonathan.

He received his B.A. in 1960 from the University of Utah. In 1965 he earned his Ph.D. at Stanford University, under the direction of Donald P. Abbott. His thesis used the functional and comparative anatomy of opisthobranch gastropod reproductive systems to elucidate the phylogeny of the group (Ghiselin, 1966a). While he was a graduate student, he visited the Seto Marine Laboratory, Japan, where he was photographed in the intertidal zone by Dr. Kikutaro Baba. His research was on the functional and comparative anatomy of the ringiculoidean heterobranch Metaruncina setoensis (Baba, 1954) (Ghiselin, 1963).

Mike was a Postdoctoral Fellow at Harvard University (1964-1965), where he studied with the renowned evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr. He then became a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Marine Biology Laboratory, Woods Hole, until 1967 when he was appointed Assistant Professor at the University of California, Berkeley. He was chosen as a Guggenheim Fellow (1978-1979), and then served as a Research Professor of Biology at the University of Utah (1980-1983). He received the prestigious MacArthur Foundation Grant (“the genius award”), serving as a MacArthur Prize Fellow from 1981 to 1986. Starting in 1983, Mike was a Senior Research Fellow at the California Academy of Sciences.

Dr. Ghiselin was primarily an evolutionary biologist, whose research interests crossed a broad swath of disciplines. The foundational concept of biology is evolution, the historical development of life over time. As Theodosius Dobzhansky (1973) wrote, "Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.” To Mike, that was the only way to study the science of living organisms, which he did brilliantly. Evolution was the starting point for the multiple themes of his research and writings

As Michael explained (2007), “I began my professional career as a comparative anatomist, and wrote my doctoral dissertation on the reproductive systems and phylogeny of opisthobranch gastropods, a group upon which I still do some research. This work aroused my interest in the fundamental principles of systematics and the history and philosophy of biology. Much of my theoretical work has been focused upon the basic units in biology, especially the species, and their role in evolutionary thinking. It turns out that this work has broad implications and I have addressed some of these in my publications on philosophy, linguistics, developmental and cognitive psychology, and sociobiology....More generally, I have been led to believe that biology and economics are basically the same branch of knowledge. I have done much work in an attempt to synthesize the two disciplines.”

Following is a brief summary of his work and writings, which we have divided into five major topics. This is in no way meant to be exhaustive, but representative of the depth and brilliance of his contributions.

History of Science. Mike’s historical publications dealt primarily with Darwin; his first book was The Triumph of the Darwinian Method (Ghiselin, 1969a). In 1980 he received the Pfizer Award, given annually by the History of Science Society, for this book. Mike co-edited a volume dedicated to the influences of Darwin on studies of the Galapagos (Ghiselin & Leviton, eds., 2010), and he published a comprehensive bibliography of published resources on Charles Darwin’s life and thoughts (Ghiselin, 2009). Around 1872, the German Darwinist Anton Dohrn founded the Stazione Zoologica di Napoli (SZN) to create a first-rate laboratory for the study of evolution. He succeeded, and scientists from all over the world flocked to it. Darwin wrote Dohrn, saying the station was ‘‘a great service you have conferred on Science’’ (Groeben, 1982, p. 67). Ghiselin first visited the SZN for two months in 1968, researching primary historical sources in the library on the influence of the theory of evolution on 19th century embryology. His continued affiliation with the SZN resulted in several publications, including a translation and discussion of Dohrn’s work on the evolution of vertebrates (Ghiselin, 1994), and a history of the SZN and its impact on Italian zoology (Groeben & Ghiselin, 2000). In addition to his long tenure as a Senior Research Fellow at the California Academy of Sciences, Mike founded the Center for the History and Philosophy at the Academy.

Sexuality and Reproductive Anatomy. Michael’s thesis gave him a solid base for the study of the evolutionary history of sex. Examining hermaphroditism (Ghiselin, 1969b) he proposed that this feature may evolve in certain conditions, such as when it's difficult to find a mate, when one sex benefits from being larger or smaller than the other, or when populations are small and genetically isolated. Ghiselin proposed two major hypotheses to explain the evolution of hermaphroditism in animals, the low-density model and the size-advantage model. His ideas on the evolution of sex were more fully explained in his book, The Economy of Nature and the Evolution of Sex (Ghiselin, 1974a). He also described the historical origins of our ideas on hermaphroditism (Ghiselin, 2006) and on the evolution of sex (Ghiselin, 1988). In Mike’s own inimitable words, “I am one of the few people who can make sex boring!”

Philosophy of Science. His main philosophical research efforts concerned the principles of classification, analyzing systematics and taxonomy (e.g., Ghiselin, 1966b, 1985, 1995, and 2004). He examined the phylogenetic classification in Darwin’s monograph on the barnacles (Ghiselin & Jaffe, 1973). He revolutionized taxonomy with his idea that species are individuals (Ghiselin, 1974b), which he later expanded upon in his book on the philosophy of evolutionary biology (Ghiselin, 1997). The book's primary focus is on species and speciation, but it deals with a wide variety of other concepts, including a reexamination of the role of classification in biology and other sciences.

Bioeconomics. Mike studied this multi-disciplinary theme early in his career (Ghiselin, 1974a). When the first academic chair of bioeconomics was established at the University of Siena, he was the first to occupy that position. In 1998 he was an original co-editor of the Journal of Economics. He was an invited speaker at the International Congress on Evolution: Intersecting Natural and Social Sciences at the University of Siena (December 2009). He wrote about bioeconomics and the metaphysics of selection (Ghiselin, 1987), examined the bioeconomics of folk and scientific classification (Ghiselin & Landa, 2006), looked at sexual selection from a renter’s viewpoint (Ghiselin, 2016). His bibliography of bioeconomics contained some 1000 references (Ghiselin, 2000).

Evolutionary Chemical Ecology. Mike was incredibly pleased when an obnoxious chemical metabolite from a nudibranch was named in his honor (Hochlowski et al., 1982). This personal connection may have given him the impetus for his interest in the evolution of protective chemicals secreted by the Heterobranchia. His first paper on this topic (Faulkner & Ghiselin, 1983) described the evolution of chemical defense among the dorid nudibranchs. He also described the evolution of chemical defensive methods among the Sacoglossa (Cimino & Ghiselin, 1998), and terpenoids from Hexabranchus sanguineus (Zhang et al., 2007). His major synthesis described the evolution of chemical defense among all the opisthobranchs (Cimino & Ghiselin, 2009).

FIELD WORK

Mike first became fascinated with the ocean dating back to his youth, spending his summers in Laguna Beach where he snorkeled and went spear-fishing. From intertidal rock-rolling, to snorkeling and scuba diving, Mike was a true globe-trotting field biologist. As a graduate student, Mike participated in Stanford’s expeditions to the tropical Pacific aboard the sail boat Te Vega to exotic locations around Indonesia and Malaysia. While at UC Berkeley, he spent most of his time in Bodega Bay, with a. bayside house, where he worked at the Bodega Marine Laboratory. In collaboration with several colleagues (Barbour et al., 1973) he produced a significant volume on the ecological relationships within the various terrestrial and marine habitats on Bodega Head.

Hans certified Mike as a PADI Open Water Scuba Diver in September 1982. His final check out dives were at Bahía de los Ángeles.

In 1984, with funding from the George Lindsay Field Research Fund, Mike, Hans and Terry participated in two international reconnaissance expeditions (Bertsch, 1985) with staff, faculty, and students from CAS, Ciencias Marinas (Universidad Autónoma de Baja California), and CICESE (Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada). We drove over paved and dirt roads, and across mirage-filled sand flats, stopping to dive at sites in Baja California Sur, from Punta Eugenia, Bahía Tortugas, Loreto, Isla Magdalena, and Las Cruces to the sand falls in the canyon at Cabo San Lucas. We found over 30 species of slugs, including the expected tropical or temperate species (including “Hypselodoris” ghiselini) and the unexpected new species or range extensions. All this, despite over five flat tires, a busted body frame twice on the same vehicle (requiring welding), a blown radiator, and Mike’s returning to camp with a cholla branch stuck to his arm. But every morning’s campsite was awakened by Mike handing each of us a hot cup of coffee, while we were still in our sleeping bags.

A few years later Tom Smith (of Ardeadoris tomsmithi fame) joined Mike and Hans on a dive trip down the peninsula. We spent time at Bahía de los Ángeles and dove with Miguel Quintana at Mulegé. A side trip into the valleys west of Mulegé resulted in our rediscovering a long lost petroglyph site, first described by the French explorer Leon Diguet in 1895 (see Bertsch, 1992). ]

Of course, as a Senior Research Associate at the CAS, he participated in numerous expeditions to the Mexican Caribbean (1985, 1989) and the far western Pacific, including Madang, Papua New Guinea (1986, 1989, 1992), Palau (1994), and the Philippines (1995, 1996).

MENTOR, COLLEAGUE, AND BELOVED FRIEND

Terry Gosliner and Gary Williams met Mike at UC Berkeley in 1969 as sophomores in Biological Sciences. Mike actually organized an office for these undergraduates at the Bodega Marine Laboratory to set up their typewriters and work on new species descriptions of intertidal animals that they had discovered from California to Baja.

Mike was Hans’ major professor and Ph.D. thesis director (1971-1976).

We will always remember Dr. Michael T. Ghiselin as a great mentor, brilliant scientist, esteemed colleague, and beloved friend. Here’s to you, Mike!

Literature Cited

Barbour, Michael G., Robert B. Craig, Frank R. Drysdale & Michael T. Ghiselin. 1973. Coastal Ecology: Bodega Head. Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press. Xix + 338 pp.

Bertsch, Hans. 1985. An international reconnaissance expedition: Marine zoogeography of Baja California Sur. Environment Southwest 508: 18-23.

Bertsch, Hans. 1992. A description of Diguet's Site 12, Baja California Sur, Mexico. In: Hedges, Ken (ed.), Rock Art Papers Volume 9. San Diego Museum Papers No. 28: 1-4.

Cimino, Guido & Michael T.Ghiselin. 1998. Chemical defense and evolution in the Sacoglossa (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Opisthobranchia). Chemoecology 8(2): 51–60.

Cimino, Guido & Michael T. Ghiselin. 2009. Chemical Defense and the Evolution of Opisthobranch Gastropods. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 60(10): 175-422.

Cronin, Greg, Mark E. Hay, William Fenical & Niels Lindquist. 1995. Distribution, density, and sequestration of host chemical defenses by the specialist nudibranch Tritonia hamnerorum found at high densities on the sea fan Gorgonia ventalina. Marine Ecology Progress Series 119(1-3): 177-189.

Faulkner, D. John & Michel T. Ghiselin. 1973. Chemical defense and evolutionary ecology of dorid nudibranch and some other opisthobranch gastropods. Marine Ecology Progress Series 13(2-3):295-301.

Ghiselin, Michael T. 1963. On the functional and comparative anatomy of Runcina setoensis Baba, an opisthobranch gastropod. Publications of the Seto Marine Biology Laboratory 11(2): 389-398.

Ghiselin, Michael T. 1966a. Reproductive function and the phylogeny of opisthobranch gastropods. Malacologia 3(3): 327-378.

Ghiselin, Michael T. 1966b. An application of the theory of definition to taxonomic principles. Systematic Zoology 15(2): 127-130.

Ghiselin, Michael T. 1969a. The Triumph of the Darwinian Method. Berkeley and London, University of California Press. 260 pp.

Ghiselin, Michael T. 1969b. The evolution of hermaphroditism among animals. The Quarterly Review of Biology 44(2): 189–208.

Ghiselin, Michael T. 1974a. The Economy of Nature and the Evolution of Sex. Berkeley & London, University of California Press. 346 pp.

Ghiselin, Michael T. 1974b. A radical solution to the species problem. Systematic Zoology 23(4): 536-544.

Ghiselin, Michael T. 1985.Mayr versus Darwin on paraphyletic taxa. Systematic Zoology 34(4): 460-462.

Ghiselin, Michael T. 1987. Bioeconomics and the metaphysics of selection. Journal of Social and Biological Structures 10(4): 361-369.

Ghiselin, Michael T. 1988. The Evolution of Sex: A History of Competing Points of View. In Richard E. Michod & Bruce R. Levin (eds.), The Evolution of Sex: An Examination of Current Ideas. Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer Associates, 1988. Pp. 7-23.

Ghiselin, Michael T. 1994. The origin of vertebrates and the Principle of Succession of Functions. Genealogical sketches by Anton Dohrn 1875. An English translation from the German, introduction and bibliography. History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 16: 3-96.

Ghiselin, Michael T. 1995. Ostensive definitions of the names of species and clades. Biology and Philosophy 10(2): 219-222.

Ghiselin, Michael T. 1997. Metaphysics and the Origin of Species. SUNY Series in Philosophy and Biology. Albany, State University of New York Press. 377 pp.

Ghiselin, Michael T. 2000. A bibliography for bioeconomics. Journal of Bioeconomics 2: 233-270.

Ghiselin, Michael T. 2004. Mayr and Bock versus Darwin in genealogical classification. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research 42(2): 165-169.

Ghiselin, Michael T. 2006. Sexual Selection in Hermaphrodites: Where Did Our Ideas Come From? Integrative and Comparative Biology 46(4): 368-372.

Ghiselin, Michael T. 2007. Autobiographical comments. https://researcharchive.calacademy.org/research/curators/ghiselin.php \

Ghiselin, Michael T. 2009. Darwin: A Reader's Guide. Occasional Papers of the California Academy of Sciences 155: 1–185.

Ghiselin, Michael T. 2016. What is sexual selection? A rent-seeking approach. Journal of Bioeconomics 18: 153-158.

Ghiselin, Michael T. & Linda Jaffe. 1973. Phylogenetic classification in Darwin’s monograph on the sub-class Cirripedia. Systematic Biology 22(2): 132-140.

Ghiselin, Michael T. & Janet T. Landa. 2006. The Economics and Bioeconomics of Folk and Scientific Classification. Journal of Bioeconomics 7: 221-238.

Ghiselin, Michael T. & Alan E. Leviton (eds.) 2010. Darwin and the Galapagos. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 61 (Supplement 2): 260 pp.

Gosliner, Terrence M. & Michael T. Ghiselin. 1987. A new species of Tritonia (Opisthobranchia: Gastropoda) from the Caribbean Sea. Bulletin of Marine Science 40(3): 428-436.

Groeben Christiane (ed.). 1982. Charles Darwin, 1809–1882, Anton Dohrn, 1840–1909: Correspondence. Napoli: Macchiaroli.

Groeben, Christiane & Michael T. Ghiselin. 2000. The Zoological Station at Naples and its impact on Italian zoology. In: Giovanni Canestrini Zoologist and Darwinist. Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti. Pp. 321-347.

Hochlowski, Jill E., Roger P. Walker, Chris Ireland, and D. John Faulkner. 1982. Metabolites of four nudibranchs of the genus Hypselodoris. Journal of Organic Chemistry 47:88-91.

Korshunova, Tatiana & Alexander Martynov. 2020. Consolidated data on the phylogeny and evolution of the family Tritoniidae (Gastropoda: Nudibranchia) contribute to genera reassessment and clarify the taxonomic status of the neuroscience models Tritonia and Tochuina. PloS ONE 15(11): 47 pp. e0242103. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0242103.

Zhang, Wen, Margherita Gavagnin, Yue-Wei Guo, Ernesto Mollo, Michael T. Ghiselin & Guido Cimino. 2007. Terpenoid metabolites of the nudibranch Hexabranchus sanguineus from the South China Sea. Tetrahedron. 63 (22): 4725–4729.

; Hans Bertsch Terrence M. Gosliner

hansmarvida@sbcglobal.net tgosliner@calacademy.org

|

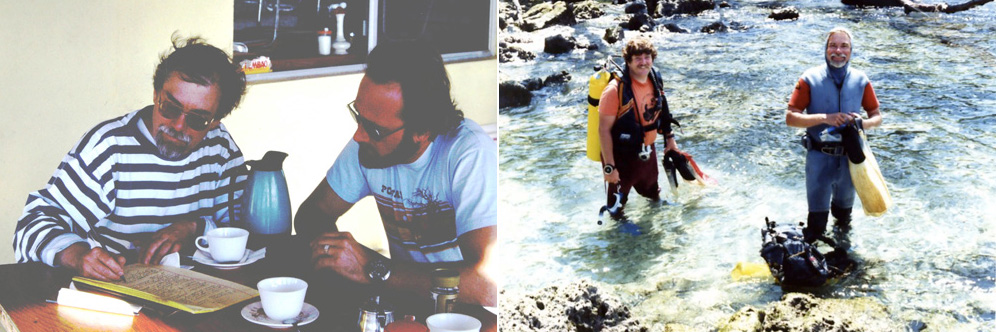

Mike and Hans at Bahía de los Ángeles, 28 February 1989 (Photo to the left)

Mike and Terry and Papua New Guinea, 1986 (Photo to the right)