Corambe pacifica

Corambe pacifica MacFarland and O'Donoghue, 1929

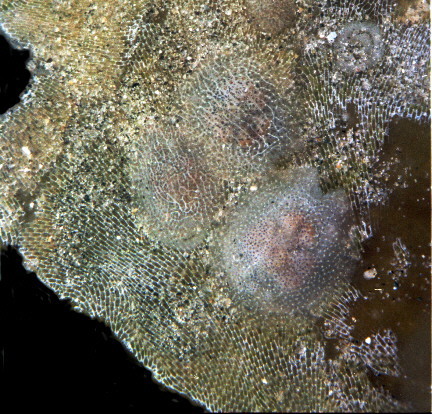

Mike Miller and I were diving together for the first time in the United States at La Jolla Shores (San Diego, California), a sandy habitat verging upon deep canyons. I picked up a piece of loose Macrocystis algae that was drifting back and forth with the wave currents. On it I saw the encrusting white bryozoan Membranipora, and the coiled eggs of a nudibranch. Looking more closely, I quickly spotted the distinctive gentle bump of the nudibranch Corambe pacifica. At the time I was not sure whether it was Corambe or Doridella. Only examination of Mike's photo allowed me to identify it several days later. With age, my vision has not improved!

Anyway, during the dive, I knew slug creatures were on the bryozoan, so I motioned to Mike to photograph the loose piece of algae. He looked quizzically at me, humored me with 4 or 5 shots, and then moved on. I don't think he realized what he was photographing. But his photograph (see above) is clearly excellent, so he'll take credit for it after all.

The point of this lengthy "dive tale" is to introduce one of the more well- camouflaged slugs in existence: Corambe pacifica.

It is rather small, only reaching about 15 mm in total length. Its body coloration and texture mimics its prey item, Membranipora. As Frank Mace MacFarland wrote (1966): "A more perfect example of protective coloring would be difficult to find as this animal so perfectly matches its habitat in markings and color." It is translucent gray, with brownish netlike markings that mimic the zooecia of its bryozoan prey.

This species ranges from Sitka, Alaska, to the middle of the Pacific coast of Baja California (Estero de Coyote), Mexico.

It closely resembles another byrozoan feeding nudibranch, Doridella steinbergae (Lance, 1962), but can be distinguished readily by two external features: Corambe pacifica has a notch in the rear of the dorsum from which protrude the gills, and its rhinophores have vertical ridges. In contrast, Doridella steinbergae lacks the posterior dorsal notch and has smooth rhinophores.

Harvell (1986) published a marvelous ecological study on the bryozoan's induced defense mechanism when Coramb eats it. He found that within 36 hours of being attacked by the nudibranch, the bryozoan grows large, chitinous spines. This defensive growth is apparently triggered by chemicals released from the nudibranchs into the water. Hence parts of the colony some distance from the nudibranch will also grow this defense mechanism. This is an excellent example of cost-benefit analysis in evolutionary ecology theory. On spined colonies the nudibranchs ate only 40% as much of the bryozoan as those on the non-spined prey. However, the bryozoan had to sacrifice something in exchange for this slight protection. The spined colonies grew at only 85% of the rate as the non-spined colonies. This is natural selection--the differential survival of offspring, or the survival of the slightly fitter--a bit of an advantage in not being eaten as much, is gained by a bit of a loss in growth capability.

So the next time you are kelp diving (or sand diving and see a wayward kelp frond float by), stop and check for the eggs of these cryptic nudibranchs. Then try to find the animals!

REFERENCES

Harvell, C.D. 1986. The ecology and evolution of inducible defenses in a marine bryozoan: Cues, costs, and consequences.American Naturalist 128: 810-823. MacFarland, F.M. 1966. Studies of opisthobranchiate mollusks of the Pacific coast of North America. Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences VI: xvi + 546 pp.

TEXT BY DR. HANS BERTSCH

Photo by Herr Mike Miller!!!

192 Imperial Beach Blvd. #A |